by David Smith, Gonzalo Lizarralde, Lisa Bornstein, Benjamin Herazo, Trent Bonsall, and Steffen Lajoie*

1. Adapting to global warming is not enough: Comprehensive disaster risk reduction, based on recognition of social and environmental injustices, is required in informal settings in the region.

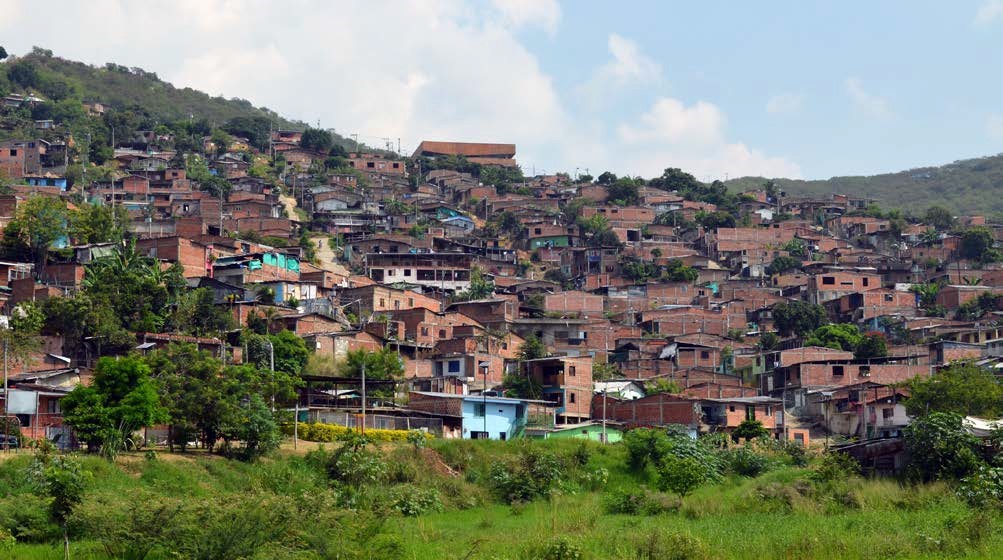

The choices and actions of leaders and residents in informal settings show that the climate agenda in the region must address both social and environmental injustices. In fact, the 22 initiatives had remarkably diverse objectives, responding to specific needs and the cascading effects of multiple local threats. This observation challenged our initial conception of the types of projects that enhance “adaptation” to climate change. We concluded that the scope of climate action must be expanded, from hazard-focused approaches (e.g., focusing on sea level rise alone) to approaches aiming to respond to people’s daily struggles, such as crime, unemployment, and lack of food and water.

A few local initiatives focused on reducing people’s physical vulnerability to hazards (see for instance Resilient Housing Through Community Self-Management and Sustainable Urban Drainage System). However, local leaders and community members often wanted to do more than just adapt to global warming. They wanted to reveal and redress social injustices, reduce economic vulnerability, and preserve natural ecosystems. As such, they often widened the scope of initiatives beyond what might be considered a typical “climate response.”

Residents and leaders connected climate risks with their daily struggles. They linked their vulnerability to climate risks with social injustices, such as inequality, poverty, and food insecurity. In fact, many initiatives in Colombia and Chile aimed at reducing unemployment and food insecurity (see Pottery Workshop and Community Gardens). Residents believe that such initiatives will allow them to achieve more in the long run than immediate actions dealing only with a specific hazard[i].

Furthermore, local leaders and residents find that protecting fauna and flora from human activities is as important as protecting human settlements from natural hazards. In keeping with their vision of environmental justice, they advocate for protecting and restoring natural ecosystems affected by human actions (see Reforesting Yumbo, Forest Therapy, and the Coastal Marine Festival). Residents believe that preserving ecosystems is key to reducing risks and working toward ecosystem restoration helps mitigate extreme climate variations[ii].

[i] United Nations & World Bank (2010). Natural Hazards, UnNatural Disasters: The Economics of Effective Prevention.

[ii] Pörtner, H.O. et al. (2021). Scientific outcome of the IPBES-IPCC co-sponsored workshop on biodiversity and climate change.

2. Trust between stakeholders is often the basis for positive change. However, trust between governments and people living in informal settings is often elusive and fragile. Facilitative, structured dialogue, among other participatory approaches, takes time but can help break implementation barriers and establish common ground.

Establishing trust and finding common ground between residents in informal settings, local leaders, government representatives, researchers, and other partners is a prerequisite for effective climate action. However, these stakeholders are often unaccustomed to working together and may not trust one another. In some cases, internal division, and suspicion within the local population hamper engagement. In other cases, citizens in informal settings are wary of participatory activities, having often suffered from the indifference and manipulative behaviors of political and economic elites. In Cuba, top-down decision-making by the state typically leaves little space for community input. In Colombia, patronage, clientelism, and corruption are hallmarks of local governance culture. This culture is despised by residents and local researchers alike. Finally, in Chile, political polarization, demonstrations, and political repression hinder community engagement. These problems are often rooted in racism, patriarchal structures, elitism, systemic marginalization, and other social injustices. All are real obstacles for climate action in informal settings.

During implementation, local leaders and researchers developed and tested new methods for stakeholder engagement that were specific to local governance conditions. The participatory approaches we adopted, brought under the umbrella term “structured dialogue” by our Chilean partners (conversación disciplinada in Spanish), sought to establish trust, develop empathy, and generate lasting relationships. Structured dialogue also helped us create common meanings, break down systemic barriers, and consolidate partnerships between stakeholders who normally do not work together. Structured dialogue and other participatory approaches are demanding. In almost all cases, local leaders and project partners spent a lot of time fostering relationships with authorities and business networks. These efforts were necessary to establish trust, mobilize resources, and initiate local action. In some cases, this work took more than two years (see for instance Sustainable Urban Drainage System in Yumbo). This duration contrasts with the typically short project timeframes used by funding agencies, usually in the aim of showing results quickly and seizing opportunities[i]. But we found that acting fast may erode local leaders’ trust and alienate local representatives (see for instance Vertical Community Garden). Solid partnerships are more likely to continue producing change after external funding is finished than those that have been quickly constructed. Alliances between academia, civil society groups, government, businesses, and community actors are key to transformative action in informal settings.

[i] See for instance: Hamdi, N. (2004). Small change: About the art of practice and the limits of planning in cities. London: Routledge.

3. Understanding people’s emotions in response to long-term risk, daily struggles, socio-economic concerns, disaster experiences, and climate change is key to recognizing behaviors and social injustices, engaging in dialogue, mobilizing resources, and driving change.

Many local initiatives are rooted in a strong desire to change the status quo, following sudden losses or daily struggles over food and income. Emotions regarding places, socio-economic concerns, and disaster experiences are a driving force behind citizens’ engagement in climate change adaptation and disaster risk reduction. Emotions such as pride, awe, anxiety, and anger often inspire change among leaders. Agency in the face of tragedy or injustice is not only about capacity—a term used in disaster management and academia to refer to the knowledge, skills, networks, and resources people use to deal with risk[i]. Agency also springs from people’s hopes, emotions, attitudes, aspirations, and visions for a better life.

Local leaders are often keenly attuned to people’s emotions. They use them as points of reflection, drivers of dialogue, and tools to mobilize action. Emotions are also an important component of structured dialogue between citizens and government representatives. They can be useful to inspire creative work and help develop empathy for others.

To be clear, emotions and attitudes are not simply a component of an individual’s character or behavior. They are shaped by social codes and have a political component too. Anger, frustration, annoyance, and distrust, for instance, are key components of people’s reactions to social injustices. These emotions influence and are influenced by perceptions of inequality, marginalization, racism, and elitism. As such, they are neither politically neutral nor simply an individual reaction to the environment. Aggregated, they create the social conditions in which problems are understood and possible solutions are created. After acknowledging the significance of emotions, including suffering and distress, several stakeholders focused on activities that sought to restore or heal conflicting relationships with nature (see for instance Forest Therapy). Playful and educational activities involving children became channels for formulating aspirations and discussing a collective vision of positive change (see for instance the Cuban initiatives Circle of Interest – Yo me Adapto, and Coastal Marine Festival).

[i] United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction. (2017). Terminology. https://www.undrr.org/terminology

4. Supporting and building on existing practices and activities, including those seemingly not linked to climate action per se, increases effectiveness and innovation in disaster risk reduction.

Leaders and residents of informal settings create novel and effective disaster risk reduction practices by taking advantage of existing and convenient entry points. Pottery, soccer, a cultural festival, and other activities, practices, and spaces may not seem to have any connection to climate change action to the external observer. Yet they have social and cultural value within communities and provide a solid foundation for experiments and creative solutions that can produce long-lasting transformation in informal settings. In many cases, local leaders and researchers expanded existing activities, such as cultural celebrations or gardening, to add a climate change or disaster risk component (see the Coastal Marine Festival in Cuba and the garden initiatives in Colombia and Chile). Initiatives often deployed existing local knowledge and skills that were unknown to external observers (see for instance Resilient Housing Through Community Self-Management and Managing the Risk). By building on local skills, addressing multiple risks, and consolidating existing relationships and alliances, leaders optimized resources and avoided opposition. Given that they built on knowledge, partnerships, and resources that local leaders and residents control or have access to, we believe these bottom-up initiatives are more sustainable in the long term than projects that are built from scratch.

5. Women typically lead change in informal settings, notably by creating the social fabric that allows disaster risk reduction initiatives to emerge. Yet women in the region also face violence, unwelcoming governance mechanisms, and patriarchal structures that are hard to eliminate. Supporting women in leadership roles is key to reducing social tensions and facilitating implementation.

Women living in informal settings are typically more vulnerable to climate change effects than men. Paradoxically, many of them also play crucial roles as leaders, engaging with local communities and convincing other stakeholders to commit time, money, and resources to implement change. However, leadership by local women can also be fragile. They must generally work within patriarchal systems that hinder their leadership. In places of widespread crime and bloody violence, like Colombia, women often live under physical and psychological threat.

Some women abandoned their leadership roles when bottom-up initiatives reached a political level or a higher degree of formalization, or when financial resources had to be managed (see for instance Sustainable Urban Drainage System). Engaging with politicians (often men) was arduous for some women leaders, who didn’t want their activities to be associated with a particular political party. Many women also had to deal with the indifference of male technocrats and politicians, with meetings endlessly rescheduled and calls never returned. The gap between women’s efforts and official recognition is one of the main hurdles limiting their decision-making power.

Patriarchal structures are “resilient” and hard to eliminate. Challenging deep-rooted structures takes time. Given the short timeframe of our action research project, we were not able to change them to any significant degree. In response to these multiple challenges, many women leaders preferred to work toward incremental changes from within their communities rather than adopt more confrontational approaches with authorities, which would expose them to greater risks. The extent to which such preferences are socially constructed is an open question, meriting further reflection and work.

The approaches adopted by local leaders and researchers aimed at empowering women and youth through adequate training, leadership support, tools, funding, and direct involvement in planning and implementation activities. In the short term, initiatives focused on training women on climate trends, risk management, project management, and leadership (see for instance Women of the Sea). In the longer term, several initiatives focused on raising awareness among the younger generation about gender inequalities, fostering generational change in groups ranging from elementary pupils (for instance, in the Circle of Interest Yo me Adapto) to university students (as in Chilean architectural studios, such as the Vertical Community Garden and the Pottery Workshops). Academics and practitioners can play an important role in facilitating the work of women in informal settings. The support women received from researchers and social workers helped them to engage with climate action further, and in a few cases, influence policy (see Women of the Sea). When social tensions arise (as in the SUDS and Vertical Community Garden initiatives), researchers and social workers can help establish new partnerships, rebuild trust, and support women in their leadership roles, enabling them to continue leading positive change.

6. Academic and policy jargon—often articulated around sustainability, resilience, adaptation, and other abstract notions—rarely resonates with the needs and desires of people living in informal settings. Narratives grounded in local knowledge, ideas, and practices do.

The climate and disaster risk jargon that policymakers and academics often use hardly resonates with the needs and aspirations of people living in informal settings. Government documents and politicians often adopt abstract notions that fail to consider socio-economic and cultural specificities. In Cuba, for instance, residents of Carahatas contest the relocation policy adopted in the name of climate change adaptation and sustainability. Villagers contend that relocation has negative impacts on their livelihoods and ways of life. Citizens living in informal settings often find that academic terms such as resilience, adaptive capacity, and sustainability[i] are too abstract. They find these terms confusing and feel they are disconnected from their daily realities. In contrast, narratives embracing local experiences and perspectives resonate more with people’s needs and claims. Initiatives formulated and prioritized according to local perceptions of risk and disaster can better mobilize citizens and sustain their interest (see for instance Forest Therapy). It is therefore crucial to reconcile scientific knowledge with local narratives in both research and policy. To break that communication barrier, it is fruitful to build meetings and workshops around local narratives, and to complement them with academic and professional insights. In this way, local leaders and community members can formulate their climate and disaster responses by building on their experiences, vernacular practices, and local concepts. Researchers can then avoid jargon when offering training and technical support (see for instance Women of the Sea). By mobilizing local narratives, leaders and researchers can more effectively engage in climate activism and connect long-term objectives with short-term interests and everyday challenges.

[i] United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction. (2017). Terminology. https://www.undrr.org/terminology

7. Let emotions speak, drive, and maintain climate action momentum. Informal settings are particularly unstable grounds for climate change action. Red tape, contradictions in policy, and deficiencies in infrastructure render implementation difficult—even when there is well-written policy in place.

Residents and local leaders can face significant barriers when implementing bottom-up initiatives in informal settings. National policy often targets climate action and adaptation. But deficiencies in local urban systems (such as lack of water infrastructure) abound in informal settings, rendering policy implementation difficult. For instance, obtaining authorizations and permits for local initiatives can be challenging due to complex bureaucracy and contradictions in policy (for example, construction ban policies for fishing communities coexisting with authorizations to build beach resorts and hotels for tourists). Resolving implementation barriers often requires pressuring governments to provide the necessary infrastructure and official approvals. These efforts require significant time (months of negotiation in some cases), as residents must lobby and build partnerships with relevant government and business stakeholders (see for instance Vertical Community Garden and the park-related initiatives in Yumbo).

Despite extensive lobbying efforts, governments might not build the infrastructure needed for the initiatives to be viable or they might not facilitate implementation protocols or procedures. In the face of governmental inaction, local leaders and communities are left to compensate for the lack of infrastructure with their own labor and community-driven actions. Several initiatives are in fact low-cost prototypes of more traditional infrastructure (see Sustainable Urban Drainage System, Water Management System, and Water Recovery Demonstrations). The impact of bureaucratic structures and the efforts required to compensate for deficiencies create both financial and project implementation risks. As a result, several initiatives took more time to implement than expected, and a few stalled, foundered, or failed to produce physical long-term results (see for instance Vertical Community Garden). Whether or not these “failed efforts” will have positive benefits in the long run—in the form of new alliances, understandings, or interest in renewed efforts—remains to be seen.

8. Government investment and support are often fragile in informal settings. Universities and non-governmental organizations can play a crucial role in climate action as intermediaries between authorities and citizens.

Even when community groups succeed in securing institutional investment and partnerships with government representatives, generally through extensive lobbying and dialogue, support for local initiatives can diminish or even be revoked. Fragile governance mechanisms and changing political agendas can also have a strong impact on implementation. Policymakers’ interest in supporting local initiatives can dissipate, creating tensions between or within communities (see for instance Vertical Community Garden). In some cases, politicians also try to exploit new projects to their advantage, instead of supporting bottom-up agency. Despite continuous efforts to solidify partnerships (including efforts based on structured dialogue), relationships between politicians and residents in informal settings may not be sustainable in the long run.

Local and national political agendas can also change during the implementation process. In Colombia and in Chile, for instance, leadership change after elections and social unrest resulted in the replacement of institutional representatives in existing partnerships. New institutional partners can bring different political visions and priorities, forcing local leaders to realign and renegotiate project objectives. As a result, bottom-up initiatives may take a different direction than initially planned and discussed with the original local leaders. These political factors are often beyond the local leader’s control. As stable and neutral partners, academics and non-governmental organizations can help local leaders and residents maintain partnerships with politicians. It is important, however, to be transparent with the original leaders and partners about new or changed collaborations. Social workers and academics can also help local leaders and politicians find a new common ground after social and political unrest (see Sustainable Urban Drainage System and Vertical Community Garden). These practices help reduce misunderstandings and maintain a sustained sense of ownership in local initiatives.

9. Limited means of communication and lack of information are major barriers to producing change in informal settings, particularly during crises. Mobile technology allows local leaders and residents to connect, share knowledge, and promote risk awareness.

Strikes, social unrest, and the COVID-19 pandemic severely affected the implementation of 11 initiatives. They disrupted access to information, communications between stakeholders, and visits to the locations of the bottom-up initiatives. In response, many local leaders and researchers turned to mobile technology to stay informed, communicate with others, and participate in implementation activities. In Colombia and Chile, the use of mobile technology is widespread, even in remote, marginalized, and informal settings. In Cuba, access to technology is more limited but is rapidly increasing. Researchers, local leaders, and residents have various means of connecting with one another: they may use their own computers and cellphones, or those of neighbors or institutions. In such settings, technology is essential in periods of crisis. The ability to share stories, exchange experiences and strategies, and continue working despite disruptions was key in the implementation process.

In the ADAPTO project, the use of technology was also transformative. The use of mobile technology created unexpected opportunities for training and networking. People who could not travel could still participate in disaster risk reduction activities. In some initiatives, the participation of a large regional audience generated awareness of the cascading effect of multiple hazards (see Managing the Risk). In other cases, mobile communications allowed researchers, local leaders, and residents to exchange knowledge and approaches with the community as well as with regional, national, and international audiences (see Community Social Networking Group Voces de Carahatas). The online exchange of vernacular and scientific knowledge, together with the exchange of local experiences in addressing specific problems, helped bridge the urban-rural and North-South divides. There are however limitations to reliance on mobile technology for implementing bottom-up initiatives in informal settings. Local social and support networks remain important. Initiatives such as the Coastal Marine Festival in Cuba and the Botanical Illustration Workshop in Chile relied on relationships between people and nature, and therefore could not have been implemented without in-person collaborative work. The use of technology also requires additional support for participants, such as financial help for low-income participants to buy data packages, and training for those who are unfamiliar with mobile technology.

10. A clear ethical framework that considers issues of legitimacy, appropriate governance, trust, and transparency is required for scaling impact. Bottom-up initiatives are difficult to replicate because they respond to local specificities. They require attention to detail and careful and sustained efforts over long periods of time.

Scaling impact by amplifying, replicating, or transferring good practices on a larger scale is often important for funding agencies, governments, and non-governmental organizations. However, given the complex specificities of each locality, it is crucial to frame impact within clear ethical principles that respect local capacities and values, prioritize a transparent process, and legitimize the role of local actors.

Scaling impact is rarely the most pressing issue for local leaders or residents. They are primarily concerned with immediate needs and conditions, and thus base their initiatives on local practices and traditions. They typically engage in delicate planning and execution, respecting local knowledge and specific political dynamics. The time they take to establish partnerships is often as long as the time needed to build trust between stakeholders. In this sense, the implementation of bottom-up initiatives in Cuba, Colombia, and Chile had more in common with the practice of craftsmanship than with approaches driven by a market economy logic.

Implementing initiatives was already quite demanding for local leaders. Conducting similar activities in other neighborhoods, in ways that were locally relevant, meant developing new partnerships with unfamiliar actors. Within this project’s four-year timeframe, there was not enough time to build many additional partnerships or start replicating existing ones in other locations. In addition, some women leaders showed less willingness to assume more visible roles or have their work publicized in their wider communities, reflecting both personal preferences and fears of too much exposure.

Instead of the traditional “scaling up” model, a kind of “scaling out” and “scaling in” occurred in some cases. Local initiatives generated interest within localities and regions. The training sessions and other activities generated new connections and helped mobilize new stakeholders. These collaborations remain strong in most cases. Local initiatives are now emerging in the three countries, thanks to the initial experiences and collaborations (see Women of the Sea, for instance). As the initiatives progressed, local leaders and researchers gained visibility and legitimacy in the eyes of policymakers at different levels of government. Initiatives also had an impact on local and regional policy documents (and in a few cases on national policy). Local leaders and researchers developed expertise in climate change mitigation and disaster risk reduction in their informal settlements. The fact that they are now invited to sit on planning committees and influence policy suggests that the 22 initiatives served as a step towards better disaster risk reduction action and policy in the region.

*Cite as: Smith, David et al., (2021). Lessons learned. In Artefacts of Disaster Risk Reduction: Community-based responses to climate change in Latin America and the Caribbean. Smith, David; Herazo, Benjamin; Lizarralde, Gonzalo (editors). Montreal: Université de Montréal. Accessible here: https://artefacts.umontreal.ca/