by David Smith, Gonzalo Lizarralde, Lisa Bornstein, Benjamin Herazo, Trent Bonsall, and Steffen Lajoie*

The 22 bottom-up initiatives served simultaneously as a research method and as a way to produce tangible change in informal settings. They created what we coined “artefacts of disaster risk reduction”: tangible objects and intangible spaces rooted in a deep understanding of the territory, local customs, and culturally relevant practices and rituals. These objects and spaces generated opportunities for open dialogue and established trust among citizens, local leaders, academics, business owners, and government officials. Most importantly, they allowed people in informal settings to reduce and manage the multiple risks they face.

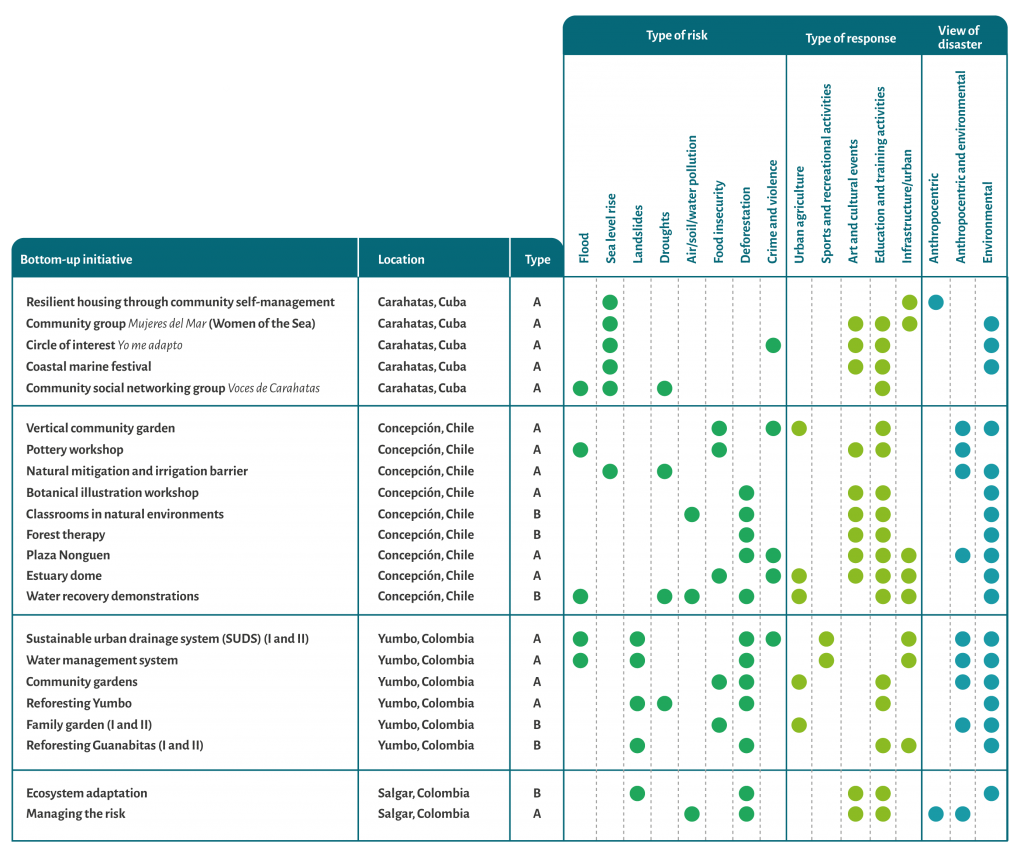

Local leaders and stakeholders designed and implemented the initiatives in response to multiple risks, including floods, food insecurity, sea level rise, landslides, erosion, water pollution, soil pollution, air pollution, heat waves, drought, deforestation, crime, and violence (see Table 1). They dealt with risk through culturally relevant activities in collective spaces, including construction, urban agriculture, recreational activities, art, education, and training. The initiatives focused on:

– Environmental protection and responses to the fragile relationships between people, the built environment, and ecosystems;

– Water management and consumption, including infrastructure for potable water, drains, reservoirs, and water collection;

– Protection of humans and the built environment from water-related hazards (floods, landslides, cyclones, tsunamis, droughts, and sea level rise); and

– Urban agriculture and food security.

Table 1. Local initiatives, including type of risk addressed and response deployed.

Carahatas: The search for continuity despite risk

[table id=5 /]

Cuba has a comprehensive climate policy called Tarea Vida that sets guidelines for intervention in risk-prone areas and establishes conditions for the relocation of settlements affected by sea level rise[i]. In addition, a national law bans new construction of houses, facilities, and infrastructure in flood-prone areas. However, residents in Carahatas and other coastal villages prefer to live with water-related risks since their livelihoods are tied to the sea. Consequently, authorities in coastal cities in Cuba now face a dilemma: whether to relocate coastal villages or allow them to remain there and be reconstructed when needed,

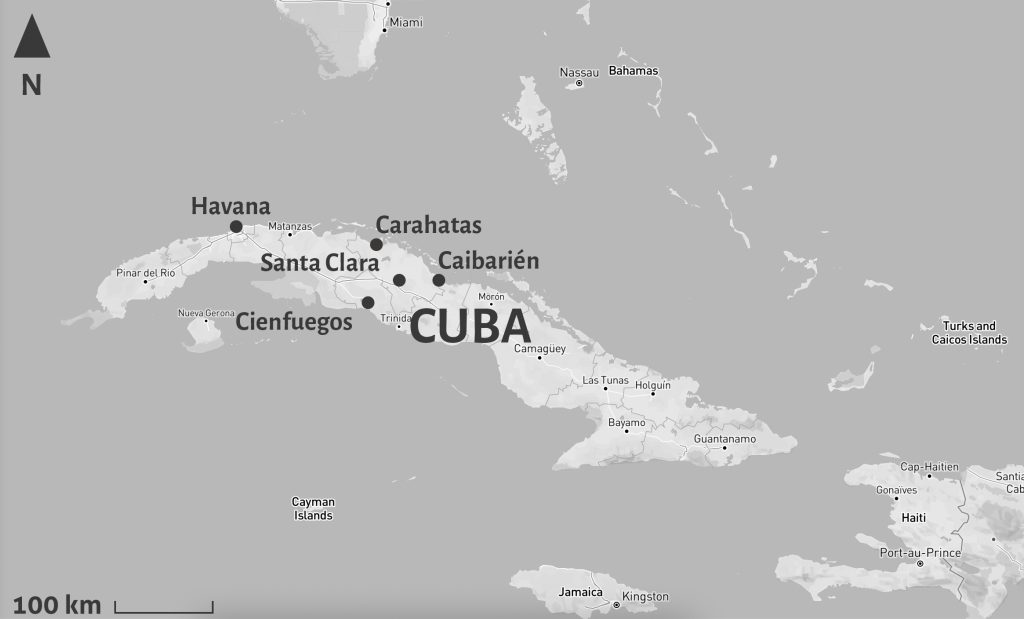

As in other nearby coastal settlements, there is a high risk of sea level rise. The settlement of about 600 people is situated near the Cayos (the Keys), a well-known tourist destination. It is part of a larger maritime ecosystem protected by the Cayos del Pajonal, Fragoso, and (further east) Cayos de Santa Maria. Carahatas is located 100 km from the inland city of Santa Clara (250,000 inhabitants), the largest city and regional center of the Villa Clara province, where the Universidad Central Marta Abreu is located.

It is estimated that 50% of the houses in Carahatas will be under water by 2050, and that by 2100 that figure could be as high as 90%. In the past few years, Carahatas has been hit by several hurricanes and tropical storms. In 2017, Hurricane Irma damaged more than 60% of the houses in the village. Residents largely depend on fishing for their livelihoods, so inland relocation, advocated by the government, is particularly contentious. Many residents fear the experience of Nueva Isabela, a fishing community that was partially moved to prefabricated five storey apartment blocks located 15 km from the coast. Carahatas residents prefer to stay near the sea and learn to live with the risks while maintaining their livelihoods, traditions, and culture[ii].

Carahatas is not an informal settlement per se. Its local governance is largely institutionalized, and residents have access to all public services offered by the Cuban state. However, the village is relatively remote and transportation to other cities is sometimes difficult, which renders access to food and goods cumbersome. Residents have very low incomes and have developed their own set of community practices and traditions. Most build and repair their own houses and collective infrastructure. Community members are in charge of running the school, local library, fishing activities, and other local services.

In the initiative Resilient Housing Through Community Self-Management, researchers from the Universidad Central brought together the local Community Architect Organization (a strong institution and in housing development in Cuba)[iii], builders with specialized knowledge and skills, residents, and local and national government officers. This collaboration made it possible to share traditional practices, technical expertise, and scientific knowledge, with a view to reinforcing local construction methods and providing better protection against climate hazards. As many as 67 houses were repaired using appropriate materials and disaster-proof techniques. The initiative served as an example of how knowledge exchange can lead to efficient hazard-proofing of buildings. This type of collaboration and approach to self-help construction contrasts with other top-down approaches to housing development adopted in Cuba, where the government typically builds turnkey apartment blocks that are then assigned to beneficiaries. The initiative has become a source of inspiration for Cuban policymakers looking for alternatives to the expensive provision of fully finished apartment units.

Three initiatives in Carahatas combined cultural events with education on climate change and awareness of environmental challenges. The initiative Women of the Sea builds on a strong cultural tradition in Carahatas: the annual Coastal Marine Festival. This event, which celebrates life close to the ocean, is now used by women to create awareness regarding environmental challenges in the region. Here, women explore culturally relevant strategies for disaster risk reduction and environmental protection. They also educate young children about ongoing and future environmental challenges. Leaders explore vernacular narratives of risk based on local knowledge and past experiences with hurricanes and other hazards, and compare them with scientific knowledge and data. By bridging the gap between vernacular and academic concepts, locals have been able to better assess risk reduction options and influence local policymakers for appropriate climate action in Carahatas. The second initiative, the Coastal Marine Festival, also uses the coastal festival as a foundation for promoting risk awareness. Here, researchers and organizers facilitated painting and literature contests, speeches, games, and performances by children geared toward the exploration of environmental and climate challenges. These activities increased awareness of the causes and effects of global warming, as well as their repercussions in Carahatas. Finally, the third initiative, a national extracurricular program at the elementary school in Carahatas, became an opportunity to teach children about risks and disasters. In the Circle of Interest Yo me Adapto, children acquired hands-on knowledge of the impact of hazards on their community and participated in recreational and cultural activities aimed at understanding environmental challenges. Following the activities, discussions at home among family members are often powerful spaces for generating awareness and influencing attitudes toward climate risk. In these three cases, we found that building on existing institutions, such as the Marine Festival and school programs, can maximize community participation, facilitate partnerships with governmental institutions, and contribute to sustaining the initiatives in the future.

A fourth initiative in Carahatas adopted a different approach. Broad access to mobile data is recent (and still rare) in Cuba. Most communications with and within Carahatas take place through conventional phone calls or in person. Therefore, communication became particularly problematic when the COVID-19 pandemic hit. Researchers and local leaders established Voices of Carahatas, a group of women who received financial support and social media training to use the newly available mobile data technology. After a few weeks, communication between the academics and local residents was not only re-established but improved. Women became very active on social media, accessing information and generating discussions on their aspirations and needs. The initiative demonstrated how access to digital communication can empower isolated communities.

[i] Nachmany, M., et al. (2015). The 2015 global climate legislation study. The Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment and the London School of Economics and Political Science.

[ii] Aragón-Duran, E., et al. (2020). The language of risk and the risk of language: Mismatches in risk response in Cuban coastal villages. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 50, 1-11.

[iii] Valladares, A. (2013). The community architect program: Implementing participation-in-design to improve housing conditions in Cuba. Habitat International, 38, 18-24; Lizarralde, G. (2014). The invisible houses: Rethinking and designing low-cost housing in developing countries. Routledge.

Yumbo: The challenge of dealing with climate risk in conditions of marginalization and violence

[table id=6 /]

In Colombia, climate-related policy builds on disaster resilience and sustainability narratives. Formal businesses and residents are expected to take action to prevent and mitigate disasters[i], while government invests in risk mitigation infrastructure[ii]. The government often sees informality as a form of illegality and urban disarray and avoids collaboration with leaders and residents of informal settlements. Low-income residents, however, see informal living and working conditions as the de facto option in the face of social injustices enacted or tolerated by political and economic elites. For these residents, climate change hinders development and increases their vulnerability due to its impacts on health[iii], food security, access to water, and agriculture. In addition, residents generally recognize that corruption hampers the creation of healthier relationships between people and their territories.

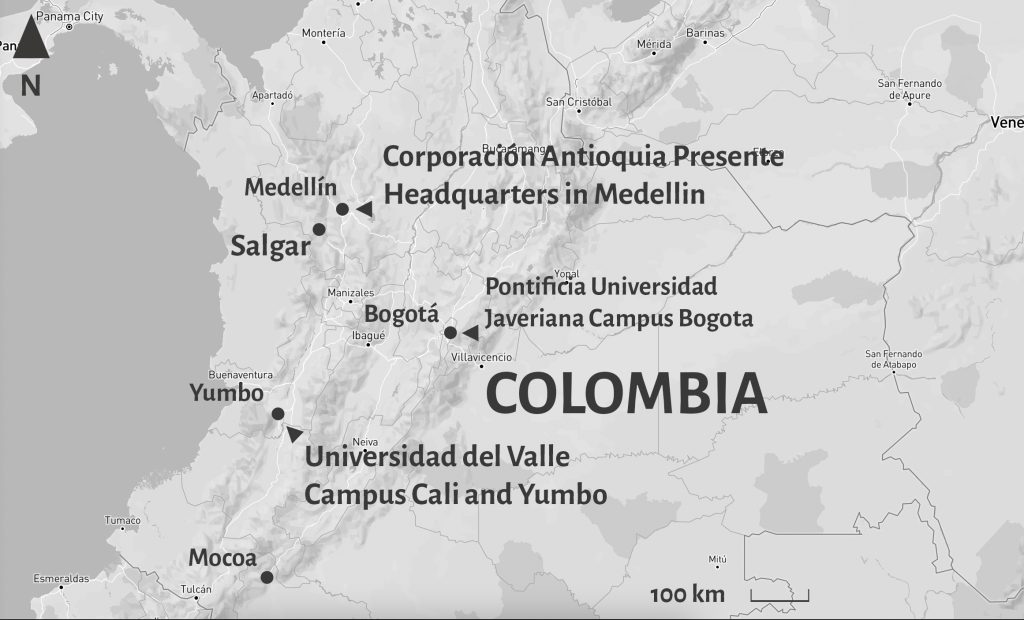

The industrial city of Yumbo has rapidly urbanized over the past 20 years and is home to thousands of citizens displaced by the 50-year-long war between the government, paramilitary groups, and leftist guerrillas. Yumbo plays a vital role in the national economy as a hub of medium- and high-skilled labor, and as a crucial transition zone between the rural communities of the Cauca and Buenaventura regions and Colombian major urban centers. While the city has a rich social and cultural fabric, it is affected by violence and crime linked to drug trafficking.

In Yumbo, thousands of informal dwellers face extreme heat exacerbated by the La Niña and El Niño phenomena and by the significant pollution caused by more than 1,000 heavy-industry plants located in the area. It is estimated that pollution in Yumbo has created a microclimate in which average temperatures are as much as five degrees (Celsius) higher than in wealthy neighborhoods in Cali, the main city located 20 km away. Informal settlements, including Las Américas, are located in areas prone to floods and landslides. In the rainy season, houses and businesses are periodically destroyed, erosion is common, and health-related problems increase.

The residents of Las Américas identified the creation of a public recreational park as a top priority. To bring the PoliPark to fruition, government approvals, materials, and labor from inside and outside the community were needed. Several initiatives were coordinated with the support of the Universidad del Valle to design, build, and equip this open space (see Sustainable Urban Drainage System, Water Management System, and Community Gardens). Women sought contributions of time, labor, and money by local businesses, organizations, and governmental institutions. Their outreach efforts helped them overcome logistical and financial barriers, as well as bureaucratic procedures, paperwork, and all-too-common corruption—all of which had made it difficult to obtain project approval. The women also organized many complementary social activities to maintain momentum and interest in the project. In contrast to the experience of partners in Cuba and Chile, some residents of Las Américas were initially reluctant to participate. However, social activities helped restore trust among residents and between them and other stakeholders. The women’s leadership and tireless work brought positive results: the park was built, and a wide-reaching partnership was forged among civil society organizations, the business sector, several governmental units, and community-based organizations.

Two initiatives—the Sustainable Urban Drainage System (SUDS) and the Water Management System—aimed to protect the new park and the communities living downstream from flooding and to provide water for the new Community Gardens in Yumbo. The two initiatives developed low-cost prototypes that compensate for the lack of stormwater infrastructure in Las Américas. The very fact that these two initiatives were needed shows that when governments fail to act or do not have the capacity to act, communities must take the initiative themselves.

The initiatives in Yumbo led to the publication of construction manuals that are accessible online, and that residents can consult for step-by-step instructions on how to implement the solutions. In addition, Colombian authorities have copyrighted the low-cost technology developed in these two initiatives. In this way, the solutions can now be implemented at a larger scale to help reduce flood risks in informal settlements located on hilly terrain. This copyright prevents private companies from exploiting the solutions commercially, making it possible for residents and academics to implement them and gain open access information about it.

The early stages of the SUDS initiative, the first to be implemented in Yumbo, were affected by tensions between neighborhood groups, local leaders, politicians, and youth gangs. The initiatives also exposed the fragility of female leadership within patriarchal systems. A few women took leadership roles initially, but stepped back when projects became political and when it became necessary to manage resources and relationships with politicians. In response, researchers from Universidad del Valle and social workers from Corporación Antioquia Presente mobilized partnerships and worked to rebuild trust with local leaders. Efficient communication between project partners and training and support for women eventually contributed to the success of the initiatives. Researchers were also helpful in finding compromises and resolving conflicts.

Accessing fresh food is difficult in Las Américas, Panorama and other informal settlements in Yumbo. The Community Gardens initiative sought to reduce food insecurity and increase environmental protection awareness through culturally relevant food production. Similarly, the Family Garden initiative encouraged residents to develop food autonomy through a series of training sessions and workshops, as well as the construction of prototypes for home gardening, composting, and solid waste sorting. Initially, leaders struggled to engage community members. But after several meetings where opportunities and ideas where shared, larger numbers of residents started to engage in planting and gardening. It became apparent that the initiative provided an opportunity for personal and collective development and this resulted in a high level of engagement. This experience reminds us that typical climate projects may not always be in line with the community’s needs, desires, and agency.

Deforestation caused by urbanization and industrial activities is a major concern for residents and leaders in Las Américas and Panorama. Two initiatives sought to raise awareness regarding ecosystem protection and tackle environmental injustices. In Reforesting Yumbo, participants created an agroforestry nursery where trees and plants could be germinated for planting throughout the neighborhoods. In Reforesting Guabinitas, participants sought to improve environmental conditions and reforest land around the water stream Guanabitas. They also offered training sessions on environmental action, and launched a communication campaign on social media to encourage residents to protect the water stream. Unfortunately, some activities in Yumbo were affected by the pandemic. However, participants continued planning, training, and networking online. They sowed plant and tree seeds at home so they could install the community garden and reforest as soon as the conditions allowed. Moving online gave local leaders an opportunity to create reusable audiovisual training and dissemination materials, while maintaining momentum on various initiatives and sustaining hope in their success.

[i] Peralta-Buriticá, H. A., Velásquez-Peñaloza, A. & Enciso-Herrera, F. (2013). Territorios resilientes: Guía para el conocimiento y la reducción del riesgo de desastre en los municipios colombianos. Federacion Colombiana de Municipios.

[ii] Páez, H., et al. (2019). Coping with disasters in small municipalities – Women’s role in the reconstruction of Salgar, Colombia.Trialog 134. A Journal for Planning and Building in a Global Context, 3(1), 9-13.

[iii] Corporación Antioquia Presente. (2019). Foro internacional: Cambio climático y desafíos en salud 2019.

Salgar: The role of bottom-up action after a major disaster and during a politized reconstruction process

[table id=7 /]

Salgar, a community of 18,000 residents in the Antioquia region in Colombia, relies mainly on agriculture. The region, located in the Andes mountains, is well known for coffee production and local entrepreneurship. The town is built along the Libordiana river as well as several streams, which regularly overflow in the rainy season. In 2015, a major landslide and rockslide, triggered by days of heavy rain, killed 104 people, and destroyed hundreds of houses. Since then, a comprehensive reconstruction and vulnerability reduction plan has been put in place, including the construction of 308 new housing units in safe locations. Authorities have also put an early warning system in place, and after consulting with local residents, they have introduced programs designed to provide them with economic, psychological, and administrative support.

The reconstruction process was shaped by competition between two opposing political leaders and parties that run separate reconstruction initiatives. The process became highly politicized, and several housing and infrastructure initiatives were overtaken by partisan interests, even as attempts were made to integrate participatory approaches. Reconstruction was achieved relatively quickly in comparison with other similar processes in Colombia. But it has not prevented new rural migrants from settling in areas close to water bodies at risk of flooding. Several residents who used to live in single storey houses and were provided with new apartment units have had to adapt to a more urban type of housing, where they have less privacy, must respect condominium rules, and are not allowed to establish home-based economic activities.

Salgar residents often have emotional connections to their land and rely on the territory and its ecosystems for their livelihoods. However, land, water, and ecosystems are increasingly destabilized by climate change. In the Ecosystem Adaptation initiative, a woman leader created a local “incubator” for environmental innovation. The goal was to boost the implementation of a series of activities aimed at increasing awareness of the natural environment and encouraging residents to take care of it. The project was a great success. In fact, most local leaders and residents find that restoring more positive relationships between people and their surrounding ecosystems can serve as the foundation for future climate change mitigation and environmental justice activities. Another initiative, Managing the Risk, seeks to promote initiatives that are already underway in the municipality but are often unknown or poorly run. Instead of designing an initiative from scratch, local leaders provided support to existing projects and networked with people and organizations to bring existing activities and expertise to light. These two cases exemplify how small, targeted initiatives, acting like acupuncture treatment, can produce significant impact on reducing risk.

Concepción region: The importance of creating social alliances for change

[table id=8 /]

The long Chilean coast, where several large cities are located, is prone to several hazards, including earthquakes, tsunamis, sea level rise, and floods. In Chile, climate change action and urban upgrading are primarily governed by national policy and institutions[i]. The Chilean Ministry of Housing and Urban Planning runs a program, Quiero mi Barrio, aimed at upgrading neighborhoods and housing. However, the political polarization and social unrest that emerged between 2018 and 2020 hindered the implementation of climate action and disaster risk reduction.

Several community leaders and low-income residents of the Bío-Bío region (near the center of the country) see neoliberalism and extractivism as the source of problems in informal settlements and denounce the environmental injustices that result from savage capitalism. They see global warming, deforestation, pollution, uncontrolled urbanization, and the destruction of ecosystems by industrial and mining activities as man-made hazards that make them vulnerable to risks[ii].

Concepción is located in a complex natural water system that includes the Bío-Bío River (one of the largest waterways in Chile), the smaller Andalién River, streams descending from Mount Caracol, a series of lakes, one water channel, and bays and peninsulas on the Pacific Ocean. The city has economic relationships with the neighboring cities of Talcahuano (a large international port on the ocean), Hualpén, San Pedro de la Paz, Coronel, Chiguayante, Penco, and Hualqui. The city makes a significant contribution to the national economy thanks to its intense port activity on the Pacific Ocean and to industrial activities, including forestry, metallurgy, and paper and energy production. Concepción has a valuable heritage of pottery production by local craftswomen and is home to top-quality universities, including the Universidad del Bío-Bío. The city is prone to floods (such as the 2006 Andalién flood), earthquakes (such as the 8.8 Mw-scale earthquake in 2010), landslides, and tsunamis. While its population doubled between 1970 and 1992, the infrastructure in many parts of the city is deficient and most informal settlements are located in flood-prone areas.

Several initiatives in the Concepción region were linked to the creative work conducted in architectural studios at Universidad del Bío-Bío. They involved asking students to prepare innovative and technical solutions, with professors and mentors acting as facilitators for interactions between leaders, residents, and university students. With input from residents and local leaders, students designed a pavilion for collective gardening (see Vertical Community Garden), craft workshops for artisans and visitors (see Pottery Workshop), a public space and a wood structure that serve as a meeting point, landscape feature, and sightseeing platform (see Plaza Nonguén), and an educational space immersed in the natural environment of a water stream (see Estuary Dome). In these initiatives, the students were invited to challenge their preconceived ideas and traditional design methods and to engage in dialogue with residents to identify women’s real needs. Several climate change initiatives were then directed toward finding solutions to enhance food autonomy, secure livelihoods, and increase environmental awareness. Training a new generation of architects in social and political subjects, including gender, is an important step toward greater social responsibility and sensitivity in architectural practice.

When the Vertical Community Garden initiative was at an advanced stage of implementation, local authorities withdrew their commitment to supply water to the garden. The built, but non-operational structure became a source of discord: community members lost trust in the initiative and tensions arose between local leaders and authorities. Thanks to dedicated social work, stakeholders agreed to dismantle the structure for a later reinstallation at another location where water could be supplied thanks to their own bottom-up initiative, Water Recovery Demonstration. These cases show that trust among stakeholders can be fragile and breaking a commitment can have major effects on local initiatives. They also show how neutral actors, such as NGOs, may help resolve conflicts that can arise in the implementation process.

These initiatives built upon a novel work strategy adopted by academics, government officers, and community members—stakeholders who rarely work together in informal settings. The approach engaged the different stakeholders in learning from each other in a process locals called conversación disciplinada (or structured dialogue). The initiatives highlighted the benefits of such collaboration—especially in the eyes of public authorities—to address the effects of climate change and disaster risks in ways that are culturally sensitive and contextually appropriate. During implementation, it was imperative to maintain communication channels between stakeholders in order to avoid misunderstandings and dissipate tension. These forms of alliances became not only an innovative work strategy but also a governance precedent. This approach has already produced tangible results: academics are already working on new initiatives with authorities, the Housing and Urban Development Service (SERVIU) and the national program Quiero mi Barrio.

In most initiatives implemented in Chile, local leaders wished to establish a new social contract and better relationships with nature following decades of neoliberal policies and industrialization. The Plaza Nonguén initiative created an outdoor educational space for teaching children about ecology and environmental issues. In the Forest Therapy initiative, local leaders organized environmental awareness activities in the forest to meet the youth’s strong desire to escape the polluted and stressful urban environment. The Botanical Illustration Workshop initiative took the form of an outdoor workshop designed to reveal and illustrate the flora of the Nonguén Valley in Chile. Unfortunately, the pandemic severely complicated the implementation of these three initiatives, which were situated in natural environments. A core goal in all these initiatives was and is to generate a moment of care, appreciation, and contemplation while in the forest—something impossible to accomplish through online activities. As a result, the local leaders put the initiatives on hold until it is appropriate to return to the outdoor locations. The fact that all the initiatives were strongly rooted in local knowledge, practices and skills is one of the main reasons why leaders and participants, young and old, maintained a high level of interest, despite the numerous obstacles they faced during implementation.

[i] Nachmany, M., et al. (2015). The 2015 global climate legislation study. The Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment and the London School of Economics and Political Science.

[ii] Inostroza, L., Palme, M., & de la Barrera, F. (2016). A heat vulnerability index: Spatial patterns of exposure, sensitivity and adaptive capacity for Santiago de Chile. PLoS One, 11(9), 1-26.

*Cite as: Smith, David et al., (2021). Our Main Results. In Artefacts of Disaster Risk Reduction: Community-based responses to climate change in Latin America and the Caribbean. Smith, David; Herazo, Benjamin; Lizarralde, Gonzalo (editors). Montreal: Université de Montréal. Accessible here: https://artefacts.umontreal.ca/