An urban vegetable garden to sow a community

by Adriana Patricia López-Valencia and Oswaldo López-Bernal. Universidad del Valle. Colombia

[table id=18 /]

Summary

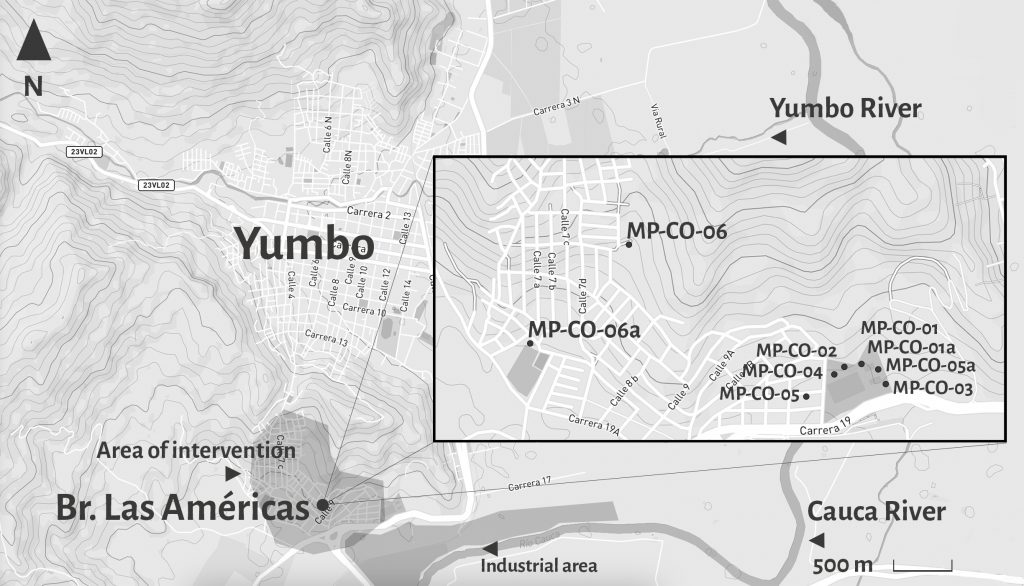

This initiative aimed to build a community vegetable garden for the new El Poli Park in the Las Américas neighbourhood of Yumbo, Colombia. In so doing, it pursued four objectives: generating a meeting place for the community, revitalizing the green spaces in the area, increasing food security, and, most importantly, enhancing the community’s capacity to adapt to climate change. Women from the community led group knowledge transfer exercises focusing on the adequacy of the site and land, soil preparation and recovery, plant care, garden management, medicinal ointments, and reforestation techniques. The Laboratory of Urban Intervention (LIUR) also took part in the initiative, contributing an interdisciplinary and collaborative approach. The final action on the site has not yet been carried out, as the spread of COVID-19 has entailed mandatory confinement. Nevertheless, community members have participated in online workshops as well as sowing activities in their own home gardens. Despite the odds, the initiative has successfully “sown” a multigenerational community of gardeners eager and ready to build the garden as soon as restrictions ease. The core lesson thus far is one of humility: we have learned that women leaders have extraordinary skills and are much better than academics at binding a community, finding solutions, and adapting to difficult circumstances.

Description

In the Las Américas neighbourhood of Yumbo, Colombia, women struggle to meet basic domestic needs, including sustaining an adequate food supply. Food insecurity is indeed one of the most pressing issues that the community faces, and youth and elderly residents are particularly affected. The neighbourhood also lacks green spaces in which to gather and find relief from the dense air pollution caused by Yumbo’s heavy industries. Air pollution, combined with the neighbourhood’s high population density, expose vulnerable residents (especially the elderly) to more extreme and more frequent climate variability, such as heat waves.

This initiative aimed to build an 80-square-metre urban vegetable garden in the future El Poli Park. It complements other ADAPTO-funded initiatives in El Poli Park. For instance, the storm tank initiative will benefit the urban garden by providing storm water. The garden can help achieve multiple objectives. Cultivating the land can alleviate food insecurity, enhance food autonomy, and offer work alternatives. The space it creates for exchange can contribute to environmental education and create strong bonds between youth and the elderly. Moreover, the expansion of green coverage can help reduce the impact of climate variability. Overall, the initiative reduces vulnerability and improves adaptive capacities to climate change.

To implement the urban vegetable garden, a group of women led and coordinated a series of activities on intergenerational education and practices. These were organized into two main components: first, plant management and use; second, low-cost sowing and planting solutions. The first component included group knowledge transfer exercises aimed at stimulating the group’s interest in gardening and raising awareness on the benefits of growing one’s own food. Based on the principle of care, these educational and practical activities brought together many children, adults (particularly women), and elderly residents. The women took on great responsibility: they took charge of a series of workshops on plant care, garden design, reforestation techniques, and medicinal ointments (Figs. 2, and 4 to 7). They also coordinated the garden project alongside other ongoing initiatives in the park, including the initiative focusing on water collectors and channels (see the local initiative “Place-making and place-protecting”). The second component was rather technical. Here, participants shared traditional low-cost strategies and methods of food production that have minimal impact on the environment and improve plant species’ wellbeing. All these activities helped “sow” trust and solidarity among participants. An added important result of this initiative was the formation of a solid network of women engaged in gardening activities.

Local Implementation and Evolution

Researchers at the Laboratory of Urban Intervention (LIUR) at the Universidad del Valle first organized a series of activities in 2017 to get to know the community of Las Américas, understand their needs, and foster a sense of trust between university partners and community members. In the end, participants defined and selected the projects for El Poli Park as a group. Members of the Fundación FACY, a local organization specializing in environmental management issues, presented the idea of an urban vegetable garden to the residents. Following the presentation, the residents selected the urban vegetable garden as a necessary climate change adaptation initiative. The ADAPTO research team assumed a leading role, forming a committee with community members, the mayor’s office, and the business sector to organize and implement several training sessions and workshops.

However, ADAPTO researchers quickly realized that they had several limitations as leaders. By assigning only participatory roles to community members, they hindered the latter group’s ability to take ownership of the management process (Fig. 3, stage 5) and caused communication problems. It was only when community members started leading the implementation of activities that the initiative gained momentum and became a collective effort. The community has since taken control of the initiative.

Unfortunately, this local initiative has not been able to gather at the park due to the COVID-19 pandemic, as public health restrictions have forced the suspension of on-site group activities. Stakeholders adapted the initiative, notably by implementing sowing activities at home instead of in the park. Thus, the initiative developed in the participants’ home gardens and online, through virtual training sessions. These activities helped maintain enthusiasm for the project despite the circumstances. As such, the participants have all contributed individually to the community garden. Interestingly, the sowing activities have had a significant snowball effect, inspiring several other initiatives. For example, sisters and community leaders Viviana and Claudia Pérez have replicated the exercise in their homes and started another ADAPTO-funded initiative (see the initiative “Sharing a family tradition”).

Stakeholder participation

Community members participated in all activities and contributed to the garden’s design; they decided what, how, and where to plant. All participants were actively involved in the activities, which shows that the initiative truly reflected their interests and needs. The women became key agents in the initiative by leading the training sessions and workshops. Moreover, they have been actively involved in all the other phases and have thus been essential figures maintaining the vegetable garden. It is important to note the extraordinary work the women leaders conducted in fundraising, networking, and management. They knocked on the doors of many businesses to ask for contributions and got the local government involved in the process. Mrs. Nidia Barona’s group of older adults also significantly contributed to the development of all group activities with their knowledge of traditional plant management techniques, natural fertilizers, water control, seeds, and land management. They also lent their meeting spaces to carry out the workshops. The environmental brigade of the Gabriel García Márquez elementary school also brought children into the fold, making the initiative truly multigenerational.

This initiative is also part of collaborative and interdisciplinary action research conducted by the LIUR and students from the Universidad del Valle. Researchers at LIUR initially led the initiative and later facilitated the technical knowledge transfer and design activities. The Universidad del Valle also helped manage financial resources and facilitated communications with external private and public stakeholders.

Private and public organizations also contributed to the initiative. The Yumbo Business Alliance and the Fundación FACY organized the “Sembrando comunidad” workshop, which focused on medicinal ointments. Private sector organizations provided lunches, beverages, and supplies such as medicinal plants. The mayor’s office participated, as the infrastructure secretary’s office organized the plowing of the area of El Poli Park for the community garden. The Municipal Environmental Technical Unit (UMATA) and the municipal council provided land and fertilizers to enable sowing.

Results

- Created a network of women interested in learning and implementing a community garden in El Poli Park.

- Organized 6 workshops for 20 women on traditional and ecological urban gardening practices.

- Generated awareness for more than 40 participants on the various benefits of urban gardening.

- Sowed 300 plant seeds in participants’ homes, due to public health restrictions (the seeds will be transplanted to the community garden at a later stage);

- Facilitated ongoing collaboration with UMATA and other partners.

Lessons learned

One key lesson learned is that gardening activities can help low-income residents better face crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Family crops have helped reduce the harsh economic vulnerability caused by public health measures of isolation and confinement.

Another lesson is one of humility. Having academics initially adopt a leading role hindered the community’s ability to take over the management of the process. It was only later, when the community took on the initiative as their own, that the activities truly kicked off. We thus learned that more control should be given to community leaders early in the process.

This finding was particularly striking in the pandemic context. In the face of adversity, we saw how women became extraordinary leaders, finding solutions to overcome barriers and reaching out to community members, government representatives, and businesses. It showed how women can be genuine leaders of change in their communities.

Future actions and replicability

Newly sown plants will be transferred to the garden when it is possible to do so. In the meantime, home sowing activities continue, and will likely continue after the creation of the communal garden in El Poli Park.