Outdoor classrooms: Recognition and care for ecosystems in the Nonguén Valley

by Claudio Araneda, Universidad del Bío-Bío

| Sponsor institution | Universidad del Bío-Bío (UBB) |

| Partner organisations | Pewma (Education with nature) |

| Developed by | ADAPTO-Chile, community and partners (see detailed list at the end of the document) |

| Professors and students | Nelson Arias (architect and teacher at Universidad del Bío-Bío) Nicolás Moraga (architect and part time teacher at Universidad del Bío-Bío). |

| Community leaders | Cinthya Veloso (initial leader) Sandra Aguilera (current leader) Juan González (environmental educator) Gerson Castillo (activist) |

| Micro-project location | Valle Nonguén, Concepción, Chile |

| Micro-project dates | 2019 – In progress |

| IDRC's base contribution Other sources of funding | CAN $4000 |

| Website | https://www.facebook.com/PewmaConlaNaturaleza |

| educacionconlanaturaleza@gmail.com |

Fig. 2. Preschool teachers and children learn and observe around a wetland. Photo: J.González

Summary

In the Nonguén Valley, urbanization is encroaching on the Pichimapu wetland. This initiative created educational spaces to enhance environmental awareness among residents of the valley. It was led by a non-governmental organization specialized in education in natural settings. Through small, specific interventions, it created outdoor “classrooms” in which children and adults alike could contemplate nature and learn about some of the animals and plants in the area. The organization installed benches and descriptive plaques, organized activities with children, and equipped two local schools with binoculars and rainproof clothes. These activities aimed to encourage learning about the natural environment, promote social and pedagogical opportunities for knowledge-building and appreciation, and recover and conserve the precious natural spaces of the wetland. In a context where children and adults spend less time outdoors and learn fewer practical skills than before, the initiative demonstrated the importance of pedagogical approaches that bring people closer to nature.

Description

The Nonguén Valley is a territory encompassing the Nonguén natural reserve as well as the farms and historical estates of the village of Nonguén. The Nonguén reserve contains the last remnants of a coastal deciduous forest in the province of Concepción. These areas are however at risk, as the city of Concepción has sprawled and reached the village, and uncontrolled urbanization has taken over the valley’s natural environment.

The Pichimapu wetland is no exception. Real estate developments already encroached five years ago when the development was built right next to the wetland, but half of it is now lost due to intensive and loosely regulated urbanization. This wetland is particularly important because it is one of the few remnants of the original landscape that once existed in the area. Moreover, it is located at the very heart of Nonguén, next to the main road, and thus constitutes one of the most important visual landmarks of the area. The wetland is also home to rich native fauna and flora, such as black-necked swans. Its value and potential for the community and for biodiversity are now reduced. Today, the wetland is flanked by a high-traffic street and two recent real estate development projects.

Juan Gonzales, Sandra Aguilera, and Cinthya Veloso, three members of Pewma, a local non-governmental organization specialized in outdoors and hands-on education in natural settings, found that the proximity of the urban area provides a unique opportunity for creating outdoor “classrooms” on the edge of the wetland. To bring children and adults closer to nature, they planned minimal interventions and actions on various sites along the edge of the wetland, to create spaces for contemplation and learning about the natural habitats. The interventions include new benches; informative signage, featuring educational descriptions of the wetland’s ecosystem along with appealing visuals; binoculars for bird watching (Fig. 1); and raincoats and boots, for students and teachers to use the educational spaces in rainy weather. The hope was that together, these small interventions and actions would encourage community members to learn about the natural ecosystems and rich biodiversity present in their neighbourhoods, and to care for them. The Pewma organizers also aimed to raise awareness on the consequences of human decisions on the fragile human-nature equilibrium.

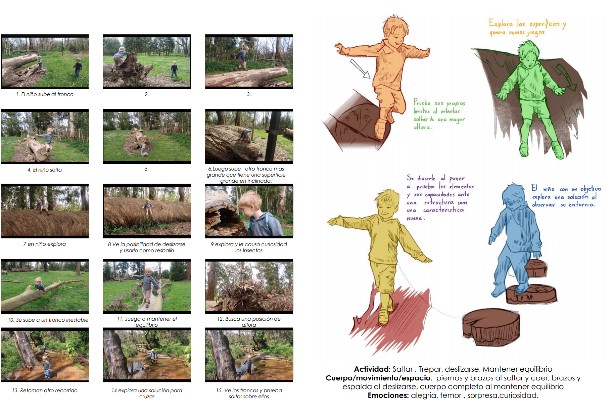

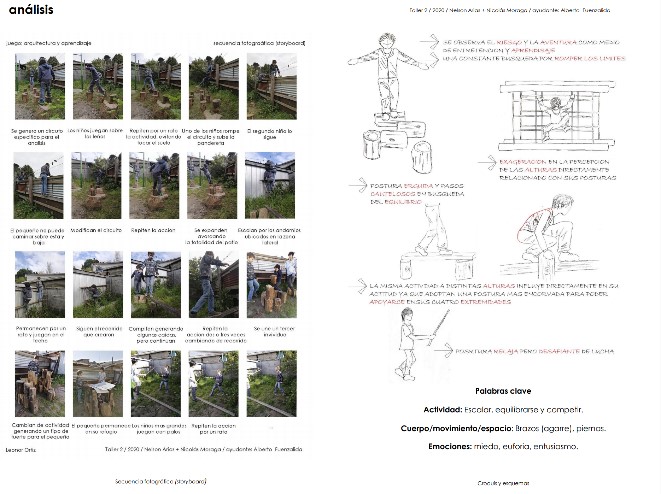

During the pandemic, the organizers also partnered with architecture professors Nelson Arias and Nicolás Moraga from the Universidad del Bío-Bío. Together, they developed a workshop with first-year students to generate designs for minimalist recreational and learning infrastructure in natural spaces. This partnership resulted in the creation of a portfolio of 41 projects that the organizers will be able to use for future interventions.

Local Implementation and Evolution

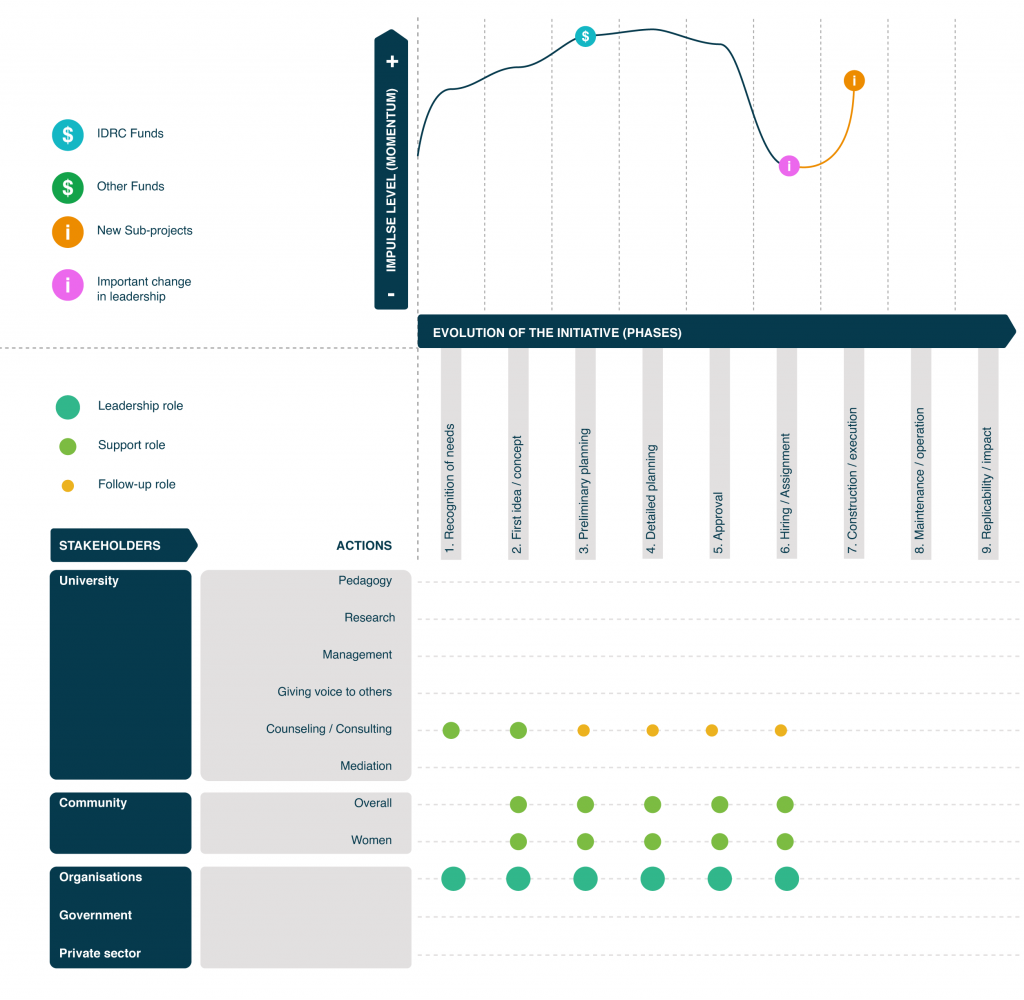

The initiative began in March 2019 with great momentum (Fig. 4), due to the Pewma team’s extensive experience with educational initiatives of this kind in the Nonguén Valley. The initial phase consisted in organizing open-air educational activities along the edge of the wetland. The team planned several educational trips (around 15 visits in total for the duration of the whole project) with children from two local schools. Children and teachers then began to produce educational plaques on the wetland birds, their habitat, and their importance for the local ecosystem. The team also built an additional bench to add seating space (see Fig. 4, 9). Children planted seeds for native plant species at the greenhouse in their school and transplanted them to the site. However, the on-site educational activities had to be suspended in late 2019 due to the mobility restrictions resulting from the mass protest movement, which saw more than 1.2 million people take to the streets of Santiago to protest social inequality. The onset of the pandemic in early 2020 forced the leaders to further suspend the activities. They planned to resume as soon as conditions permitted.

In 2020, a joint work alliance was established between Pewma and the School of Architecture of the Universidad del Bío-Bío and their Neighbourhood Studio (Taller de Barrio) initiative. This studio initiative, which aims at bridging the historical gap existing between academia, local government, and local communities, is a long-standing partner of the ADAPTO project. The architecture professors, in collaboration with the three organizers from Pewma, programmed an architectural design studio where first-year students would design playgrounds and educational infrastructure in natural environments. In online meetings with the Pewma group, architecture students analyzed videos of previous educational activities in natural environments. They then designed a set of games and learning spaces for children and in nature, based on those previous experiences. Gerson Castillo, an environmental activist who lives near the Pichimapu wetland, contributed to the students’ proposals by offering his expertise and on-site experience.

In July 2021, following the easing of COVID-19 restrictions, a group of seven residents helped clear the site and installed the last observation benches and informative/educational signage. It is hoped that this site will become a part of neighbourhood life as well as a regular component in local school curricula.

Stakeholder participation

Pewma members Cinthya Veloso, Sandra Aguilera, and Juan González led the initiative. The ADAPTO team at the Universidad del Bío-Bío facilitated the creation of the outdoor “classrooms” by contributing funding and follow-up activities by means of meetings with the leader of the initiative and visits to the site once the project was completed. Professors Nelson Arias and Nicolás Moraga of the Universidad del Bío-Bío, together with their group of 30 students from the yearly Neighbourhood Studio (Fig. 5 & 6) also provided a wealth of ideas for architectural projects to develop. Due to COVID-related restrictions, follow-up took place through regular Zoom meetings between the Pewma group and the students. The school community of the Liceo Leopoldo Lucero González has also supported the activities, with preschool children and their families participating in the activities.

The participation of the local community was also remarkable. They were first represented by a single resident living in the immediate perimeter of the wetland. Afterwards, a larger group formed, with about seven residents helping clean the site. This same group later participated in a story competition about the wetland. Afterwards, they collaborated on the preparation of an application to have this space officially declared an urban wetland, in keeping with law 21,202. The new classification is in the process of being ratified.

Results

- Created the first educational space on the edge of a wetland in Nonguen, Chile. This space is equipped with a descriptive plaque dedicated to local birds and their habitats, as well as benches built by children.

- Provided equipment to 2 local schools for outdoor learning activities with children, including binoculars and rainproof clothes for students.

- Educated 70 students from 2 local schools on environmental issues, with the collaboration of the 2 principals and 5 teachers.

- Established an partnership between Pewma and professors of the first-year architecture studio at the Universidad del Bío-Bío. Both partners are willing to continue this partnership in the future.

- Created a portfolio of 41 proposals for playgrounds and educational spaces in the natural environment of the Nonguén Valley.

- Involved 7 residents of the surrounding neighbourhoods in the activities; all are motivated to continue the activities in the Nonguén Valley once the restrictions are lifted.

Lessons learned

Educational curricula nowadays tend to privilege abstract learning over a more practical approach, and they include less hours of outdoor physical education and art (see references). Unfortunately, the global public health crisis has worsened the situation.

In contrast, we believe there is an urgent need to broaden access to environmental education on local natural habitats. Activities such as those promoted by this project, together with better coordination and promotion efforts, would help reverse this trend. Having seen the benefits of on-site, outdoors education firsthand, we hope to help establish such initiatives as part of the curriculum in local schools.

This initiative has also motivated different groups of neighbours (environmentalists, activists, elderly people, and teachers) to participate in the learning activities, and to maintain and take care of the natural spaces where the pedagogical activities are carried out. This collaboration has served to demonstrate the importance of working together. Exercises fostering appreciation for local territory have proven to be relevant learning methods in school communities, as they encourage new ways of understanding and caring for the habitat.

Future actions and replicability

The successful implementation of the project, despite the long recess due to the COVID-related restrictions, encourages us to continue on the same path. Highlighting the inherent value of natural areas, at risk of degradation due to local communities’ lack of knowledge and indifference, is indeed a path forward. We consider the enthusiastic participation of the local community’s residents and two schools to be a sign of appreciation for the project. They have also demonstrated their interest in similar initiatives.

Our hope is to make these activities an integral part of the local school’s curriculum. To this end, the ongoing collaboration with the university is key. In addition, we consider the involvement of the adult community — their experiences, their expertise, and their attachment to their habitat — as a vital component. Indeed, the adults can be an example for the children. Through them, the children can learn, value their environment, and develop a thirst for new possibilities and ways of relating to nature. This is the virtuous circle that we aim to start replicating in the future.

Additional information

Project participants

Local women project leaders:

Teresa Peña, Elizabeth Fuentes, Ana Méndez, Rosa Lawrence, Maritza Contreras, María Salas, Ruth Godoy, Solange Villarroel, Ana Pinto, Elizabeth Valencia, Michelle Faulon, Marianela Soto, Eugenia Pinto, Iris Vargas, Margarita Carrasco.

Students:

I Stage Initial project idea. Subject Project Workshop II, year 2016: Student Iliam Delgado.

II Stage Preliminary architectural project: Iliam Delgado, Luciano Riquelme.

III Stage Construction development: Camila Soto, Constanza Jara, Diego Paredes, Constanza Sáez.

IV Stage Construction and Assembly: Valentina Ceballos, Carlos Morales, Ronald Baez, Darling Quitral, Benjamin Alvarado, Iliam Delgado, Adrian Erbo, David Godoy, Felipe Castillo.

Academics and professionals:

Neighborhoods Workshop Team: Claudio Araneda, Ignacio Bisbal (4th year); Roberto Burdiles, Nicolás Sáez (3rd year); Rodrigo Lagos, Luis Felipe Maureira (2nd year); Nelson Arias, Hernán Ascuí (1st year)

Team “Quiero mi Barrio Bellavista:”

Hilda Basoalto, Alfonso Galán, Alexi Valdebenito, Jorge Méndez.

Architecture firm República Portátil:

Luis Felipe Maureira, Andrés Moreno, Camilo Aravena, Marta Villaverde, Oscar Zambrano, Martin Mansilla

Local Government Laboratory UBB:

Carmen Burdiles (Executive Coordinator), Bárbara Ojeda (UBB Social Work Internship student)

Corporación Desarrollo Conciencia – Comisión Residuos Comité Comunal Ambiental de Tomé:

Valeria Roa, Felipe Roco

References

https://elpais.com/diario/2000/11/06/sociedad/973465204_850215.html

https://www.royalacademy.org.uk/article/art-teaching-in-decline-in-our-schools