From natural to political barriers: The challenges of providing water for a community garden

by Claudio Araneda. Universidad del Bío-Bío, Chile

[table id=27 /]

Summary

This initiative was originally designed to support the construction of a natural flood barrier for a community garden project (see “Our seeds are life”), which was set to be constructed in the Bellavista neighbourhood in Tomé, Chile. A group of women gardeners led the initiative, with the support of researchers from Universidad del Bío-Bío and professionals from the Quiero mi Barrio program. The original garden site proved inadequate, thus the team moved the project to a different location that did not present the same level of flood risk. This new site was also problematic, as it lacked water supply for the community garden. The team therefore adapted the initiative to respond to the new need for water supply. Following an agreement with the municipality of Tomé, the team decided to co-finance the extension of the existing nearby water network to the site. The garden structure was built, but later the municipality retracted its commitment in order to reallocate the funds to other, allegedly more important municipal projects. The disuse of the garden caused a political reaction, eventually leading to the dismantlement of the garden structure and to the cancellation of the water supply initiative. The researchers reallocated the ADAPTO funds to assist the women gardeners in their search for a new site and in the garden’s reconstruction. This experience shows that adapting and securing alliances in the face of contingencies is paramount for the successful implementation of a local initiative. In this case, involving the neighbours living in the vicinity of the new site and keeping the alliances between the different stakeholders alive through time would have helped prevent misunderstandings and disengagement.

Description and evolution

Fig. 2. Inauguration day of the community garden on the second site. The picture shows the physical proximity of the neighbourhood

residents, who were not involved in the community garden project. They eventually asked for its dismantlement. Photo: Nelson Arias.

This initiative aimed at preparing the site that had been chosen for a community garden project in the Bellavista neighbourhood of Tomé, Chile. The community garden project (Fig. 1 and 2), also called Vertical Garden, is a collective effort by a group of women gardeners, students and researchers from an architecture studio at the Universidad del Bío-Bío, and professionals from the national Quiero mi Barrio program that aims to enhance quality of life in low-income neighbourhoods (see details in “Our seeds are life”). Located on the edge of the river Estero Collén, the original site presented several challenges. A neglected area which was subject to flooding. The first version of this initiative involved the construction of a paved site that would serve both as a natural flood barrier and as a space to sit and enjoy the surrounding landscape. However, an onsite assessment determined that the site would be too small for the project. The community garden team thus decided to change the location of the garden and to adapt the initiative to the new site’s requirements.

The new site, located further up the river, is less exposed to floods and offers a nice view over the nearby eucalyptus forest. Unfortunately, however, it does not have access to water, which is why the community garden team decided to extend the existing nearby drinking water supply network. To this end, the team met with municipal representatives on five occasions in 2019. The representatives agreed to co-finance the initiative and supply water to the site. The initiative consisted of a 100-metre pipe, which would be connected to the existing public drinking water network and would feature a tap at the end. The agreement generated great enthusiasm. The idea was simple and clear, and the commitments were firm. As a result, the community garden team proceeded to build the garden structure, convinced that water supply would come shortly after.

Unfortunately, the commitment to extend the water network never materialized. Conversations with the municipality about the implementation of the water supply extension became increasingly difficult, as interlocutors became harder and harder to reach. Some neighbours complained that the community garden structure was attracting undesired activities such as alcohol and drug consumption (see Fig. 2 and 4). At the same time, the Quiero mi Barrio program in Bellavista, thanks to which the garden initiative was made possible, had to withdraw from the initiative as its planned period of four years came to an end.

According to Hilda Basualto, leader of the Quiero mi Barrio program team, the project did not work because it was not a municipal priority, neither politically nor technically. The municipality did not understand the positive implications that the project could have had on the community. Despite efforts made by the team to convince the mayor and other municipal stakeholders, the municipality decided that the garden structure should be dismantled and moved to another location. Municipal workers disassembled the structure and stored the pieces in a local sports club. In this context, the researchers decided that the funds should be redirected to the group of women gardeners to finance the search for a new site and the reconstruction of the garden structure.

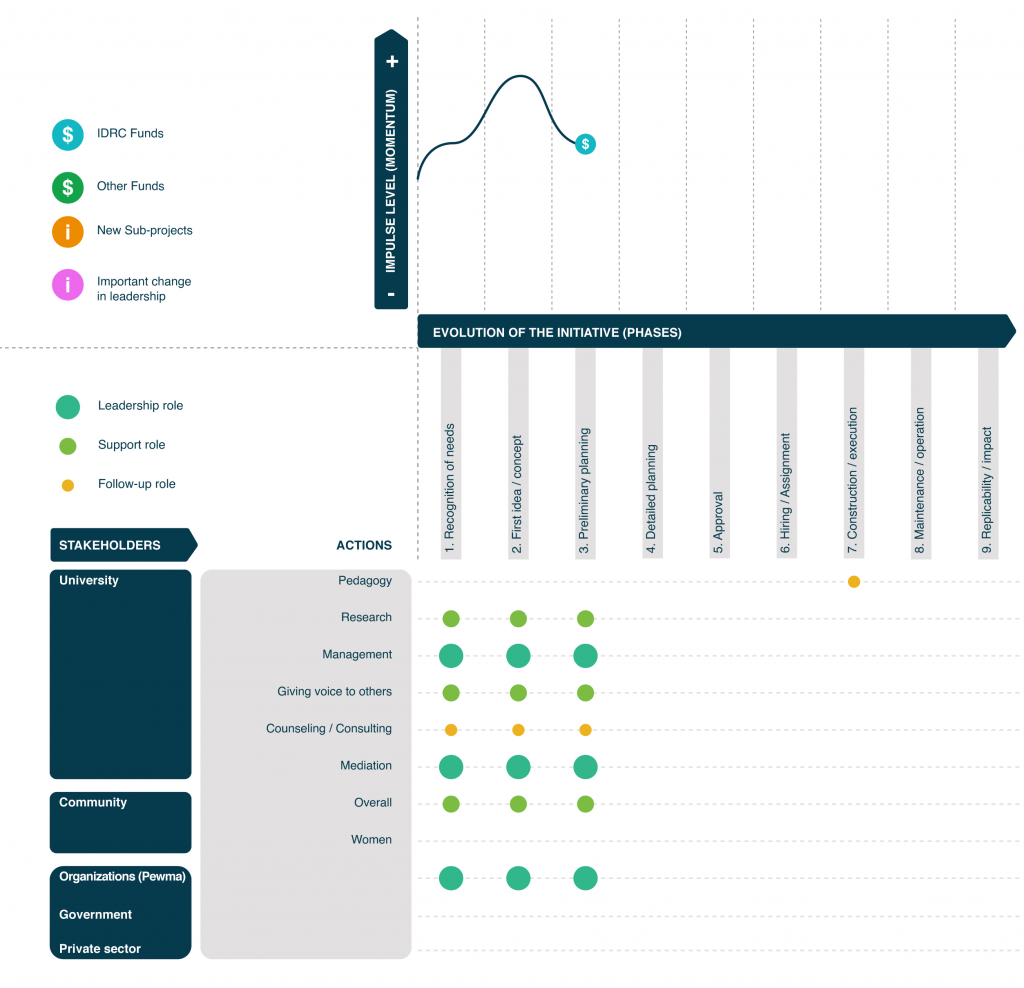

Stakeholder participation

A group of women gardeners led this initiative. Researchers from the Universidad del Bío-Bío and a representative of the Quiero mi Barrio program helped to put the team of women gardeners in contact with municipal delegates. This support was geared toward sustaining the momentum already generated by the construction of the garden at the end of the four-year Quiero mi Barrio program. The initial support of this program gave credibility to the gardeners’ demands before the municipality. This support facilitated a series of four conversations between the parties involved. Admittedly, those conversations did not suffice to bring the idea of providing water for the garden to fruition. As mentioned, we were eventually informed (unofficially) that the municipality had withdrawn its support for the idea due to lack of political and economic interest in the project.

Lessons learned

While neither the natural flood barrier nor the water supply pipe have materialized, this initiative yielded two major lessons. First, the community garden project was bound to create a rift between the women gardeners and the “new” immediate neighbours because they were not part of the group of gardeners. Thus, the team now realizes the importance of building closer collaboration with the neighbours who were stood to be directly impacted by the project earlier in the process and not only with the community of gardeners. Being directly related to the community garden project, the leaders focused on establishing good collaboration between researchers, the community of women urban gardeners, the municipal stakeholders, and the representatives from the Quiero mi Barrio program. But this was not enough. Involuntarily left out, the neighbours living in the vicinity of the garden stopped supporting the initiative as soon as problems arose. Involving them earlier in the process would have helped to find alternative solutions to keep the structure in place and bring water to the site.

Second, we noticed that municipal support declined when the Quiero mi Barrio program ended. This means that support for the project would have remained strong if the original alliances had persisted. Another lesson here is to never take for granted the importance of keeping alliances alive beyond the project life cycle—a demanding task in itself. Sustaining alliances is crucial for post-building follow-up. This presupposes efforts to keep the conversation between stakeholders alive after the project ends.

Future actions

At first glance, the idea of supplying drinking water for the irrigation of the garden made sense. However, the contestation of the neighbours, after both the construction of the garden and its dismantlement, made it clear that the initiative was inappropriate. Researchers from the Universidad del Bío-Bío also recognize that the follow-up has not been optimal since the dismantlement of the structure, largely due to mobility restrictions imposed by the pandemic. Drawing on our lessons from this experience, we—as researchers—hope to resume contact with the Bellavista team of gardeners and better help them with the reconstruction of the garden.