Our seeds are life: The recovery of a community space through the construction of a vertical garden in Concepción, Chile

by Claudio Araneda and Roberto Burdiles. Universidad del Bío-Bío, Chile

[table id=3 /]

Fig. 2. Certificate ceremony for women leaders. Photo: ADAPTO-Chile.

Summary

This initiative focuses on the construction of a vertical garden on the banks of an estuary in Tomé, a port city of 52,000 inhabitants in Concepción, Chile. The vertical garden is a pavilion for the horticulture of edible, flowering, and medicinal plants. The objective was to restore the community´s relationship with the estuary – a link broken by poor waste management practices and delinquent activities along the shore – as a first step towards better monitoring, and adaptation to flood risks in the area. The initiative aimed to strengthening women’s leadership, promoting food security, and establishing new forms of collaboration between the community, academics, professionals, and public institutions. The project began well. Partners successfully built the pavilion and trained women leaders in horticulture. However, insufficient municipal involvement and non-compliance with initial commitments hindered the planned use of the pavilion. This challenge eroded women’s leadership and community support, and, as a result, the vertical garden was dismantled. Against all odds, though, the community of gardeners – who used to be scattered and disassociated– has remained together and is currently planning to reassemble the pavilion and move forward with their activities in a different location. One of the main lessons learned is the importance of sustaining collaboration between the multiple stakeholders involved during and after the construction of a community space.

Description

This initiative is the realization of a pavilion for urban horticulture in an abandoned open space along an estuary in Bellavista, a working-class neighborhood of Tomé, a coastal city located in the Greater Concepción conurbation in Chile. This initiative constitutes the first phase of a larger proposal initiated in 2017 by student lliam Delgado as part of a “Taller de Barrios (Neighborhood Workshop)” initiative, which is a community-based architectural studio organized yearly by the School of Architecture of the University of Bío-Bío (UBB). Tapping into existing potential, such as among the numerous women who garden individually, the larger proposal originally included implementing small gardens in backyards and transforming deteriorated spaces along the estuary for urban agriculture.

The vertical garden project became part of the “Quiero Mi Barrio (I Love My Neighborhood)” program (QMB) by the Chilean Ministry of Housing and Urbanism. Through participatory processes, the program aims to enhance quality of life among residents of low-income neighbourhoods by regenerating deteriorated public spaces, improving the urban environment, and strengthening social relationships. The intentions behind this particular vertical garden initiative were: 1. To build a pavilion for the culture of edible, ornamental, and medicinal plants (Fig. 1 and 2); and 2. To promote place attachment and community engagement as a first step towards better monitoring and reducing floods risks and delinquency.

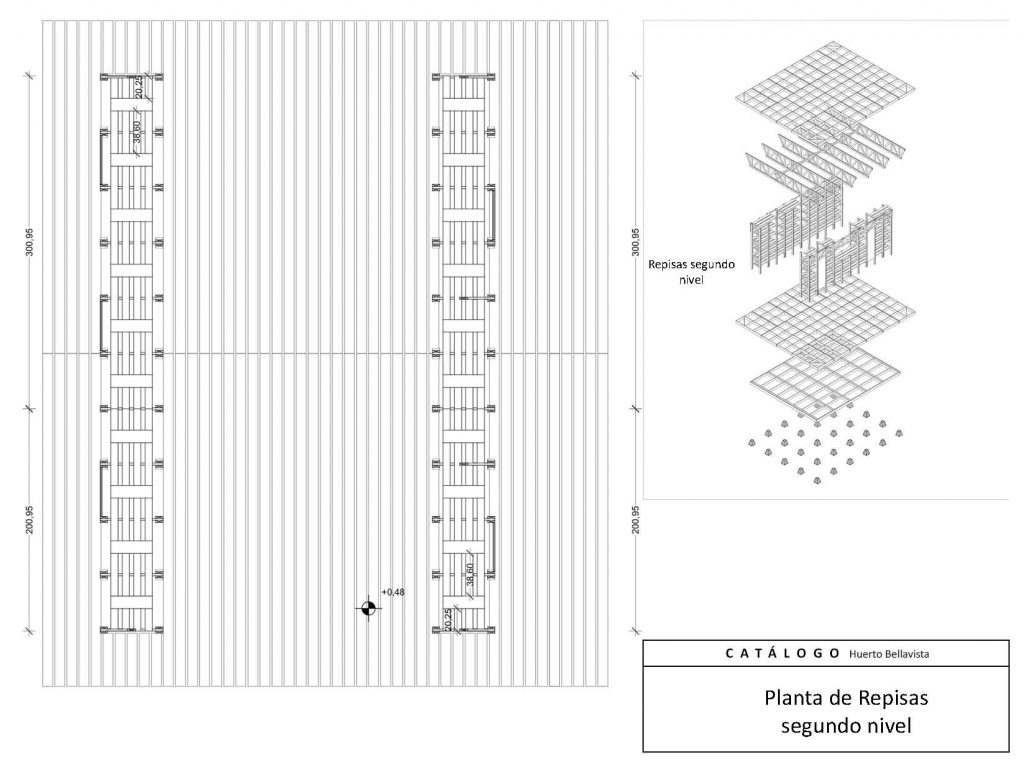

The initiative included a series of activities: design of a wood prefabrication manual for the team of students and neighbours in charge of the building process (Fig. 3); training of female community members in construction techniques and horticulture; supervision of the construction process by QMB professionals and community members; and finally, specialized training of three Bellavista community leaders in biodynamic agriculture[i] (Fig. 4). The latter – biodynamic agriculture training – took place over three days at El Molino farm in the town of Paine. The building process culminated in a ceremony to inaugurate the pavilion and to award certificates to the women who received the training (Fig. 2). Despite these successes, subsequent challenges led to the garden’s disuse and disassembly. This result is explored further in the following sections.

[i] Biodynamic agriculture is an innovative way of working the land that goes beyond organic farming. It introduces new ways of naturally fertilizing the soil as well as planting according to astrological calendars.

Local Implementation and Evolution

lliam Delgado, then a first-year student at Universidad del Bío-Bío (UBB), designed an initial architectural proposal for a vertical community garden as part of the “Neighborhood Workshop” in 2017. Iliam partnered with Luciano Riquelme, also a student, and received technical guidance from workshop teachers and local leaders. Once the academic project was finished, the architecture firm República Portátil (RP) partnered with workshop teachers and supported the students’ proposal with the development of the technical drawings. The vertical garden project then developed following the phases below.

The initial phase consisted of gradual scaling-up through collaboration between local actors (including those with knowledge of local gardening traditions and neighbourhood residents), the university (including professors and students who provided a rich portfolio of projects as part of the “Neighborhood Workshop” studio), and various public bodies (including QMB representatives and a municipal representative in charge of managing the garden’s water supply). This threefold partnership led to a strong joint proposal, which motivated the community and QMB program representatives to engage in the initiative. The enthusiasm of local leaders motivated the QMB program leaders to come up with a community initiative, titled “Our Seeds are Life,” which included the architectural proposal and other supporting community projects in the neighborhood. The initiative involved a bid for the construction of a pavilion as well as training workshops on urban gardening and medicinal plants. Fifteen women from different parts of the neighborhood participated in the process. Parallel activities, such as the horticultural workshop intended for local leaders, enhanced the community’s interest in developing and building the space to apply the newly learned skills. The most productive phase occurred once leadership and ownership of the project emerged among the different groups. For instance, the sense of ownership prompted neighborhood residents and Hilda Basoalto, chief architect of the QMB program in Bellavista, to mediate and innovate in the otherwise traditional project implementation processes. This phase culminated in the construction of the pavilion and the certification of local women leaders.

A turning point in the project came when the QMB program ended its contractual relationship with the neighbourhood. Due to its key role in sustaining municipal involvement, the end of the QMB program in Bellavista caused a loss of institutional and political support for the project. As QMB left the project, the municipality delayed implementing the irrigation system required to operate the vertical garden. As a result, the pavilion was rendered obsolete and unoccupied (Fig. 5). The abandoned project generated conflict with neighboring communities who asked the municipality to remove the garden, claiming that it was a source of public disorder and a site for drug trafficking. The group of women leaders splintered along these lines and disintegrated, but two women continued to search for solutions in order to sustain the initiative. They received support from the sustainable planning group Corporación Desarrollo ConCiencia and the Waste Commission of the Tomé Community Environment Committee. The corporation, in coordination with ADAPTO-Chile university researchers, helped to reduce community tensions and rescued the project by establishing permanent contact with the local community of gardeners. This empowered their leadership when the support from QMB receded.

Finally, the municipality dismantled the pavilion but agreed to preserve it for a later move to another location. The two organizations committed to reinstalling the garden and relaunching activities, thus opening up the possibility of replicating the idea in other contexts (as a new subproject). They were also able to re-involve the municipality in their initiative. It should be mentioned that, despite these challenges, the role of the remaining project leaders has strengthened as they continue to seek support for the project.

Stakeholder participation

This initiative is the result of a collaboration between the community of Barrio Bellavista Tomé, the Ministry of Housing and Urbanism’s QMB program, the Municipality of Tomé, and the University of Bío Bío School of Architecture. As explained, the project faced significant challenges with regard to stakeholder participation, resulting in the evolution of the project leadership over time (Fig. 6). Many of the lessons learned (see following sections) draw upon that experience.

Initially, university researchers at the School of Architecture and a professional from QMB collaborated with the municipality of Tomé to identify and support a group of women leaders in the town of Bellavista that could benefit from one of the ADAPTO initiatives. Both the university and the QMB program led the project in its early stages with the assistance of architecture firm República Portátil. Other institutions and organizations, both public and private (see Appendix A), supported the workshops. The Neighborhood Workshop and QMB stakeholders transitioned to a more supportive role over the course of the initiative, with the understanding that the local municipality would later take the lead. However, the municipality did not uphold the agreed commitment to extend the water supply to the garden site.

In a further attempt to ensure the continuity of the project, two women from the initial group of gardeners took the lead, with enhanced support from the university. Despite difficulties, including pressure from neighboring residents to dismantle the pavilion because of being used as a meeting place at night and of the lack of support from the municipality, the two women partnered with the Corporación Desarrollo ConCiencia, an NGO led by Valeria Roa. The organization became part of the project, assuming a supporting role to the two leaders. Together, they began to work on relocating the project with nominal support from the municipality. It was hoped that this new partnership would provide the necessary support to guarantee the use of the pavilion for horticulture and the continuity of the community of gardeners. Unfortunately, the municipality’s disengagement from the project, and later the ongoing Chilean protests and the global pandemic, prevented this new partnership from flourishing. However, according to the women leaders, their leadership skills have been enhanced by the numerous difficulties they faced. They said the project had become increasingly relevant to them and that it embodies their hopes to respond to the needs and aspirations of their neighbourhood.

Results

- Constructed a wooden pavilion for horticulture use with community members and architecture students, with technical assistance from República Portátil architecture firm.

- Designed a manual for constructing the prefabricated wooden structure, and distributed it to the students and neighborhood members in charge of the building process.

- Organized four workshops:

- Horticulture. Called “Our Seeds are Life,” certified and managed by the Municipality of Tomé, and dedicated to women community leaders (15 participants).

- Biodynamic agriculture. Taught to three Bellavista women leaders by expert farmers.

- Photography. Called “Workshop FAAF Bellavista 2017” by the Neighborhood Workshop initiative, and involving community members, students, and teachers (10 participants).

- Project replicability and impact analysis. Led by the local government laboratory at the University of Bío Bío for 10 students.

- Dismantled the pavilion at the request of residents and the municipality. Discussions are underway, regarding where to relocate the pavilion, with community organizers, the municipality, Corporación Desarrolla ConCiencia, and the university researchers.

Lessons learned

- Responsibility for sustaining a partnership should be shared among all partners and formalized (signed in writing, at minimum). In the case of the vertical garden project, the promise to provide water for the garden was not met, which is perhaps mainly due to the informal nature of the agreement.

- Community leadership must be empowered and given space to act; too much control from institutions can weaken autonomy, innovation, and creativity among local leaders.

- Trust takes time to build. Although great political support might be necessary to initiate the project, constant collaboration over a number of years as the project develops (three years in this case) can consolidate trust between leaders and the community and reduce the need for extensive governmental involvement in future projects.

- Architectural proposals must be flexible. Since the project may need to be displaced or replicated in new locations, it is important to have a clear construction manual, prefabricated structures, and simple assembly processes for facilitating the self-construction and deconstruction.

Future actions and replicability

In January 2020, the women leaders of the project, accompanied by university representatives, began searching for a new location to reassemble the pavilion and move forward with the planned gardening activities. At that time, they had the support and commitment of local community members who were not originally involved. Unfortunately, the pavilion still has not been rebuilt due to the public health restrictions in place as a result of the Covid’ 19 pandemic.

The lessons learned in Bellavista will be applied to the building of a new vertical garden in another location in Chile, an urban space on the edge of the Nonguén estuary. The mayor of Concepción has partnered with the University of Bío-Bío and neighborhood leaders in the Nonguén Valley to provide technical and economic support. This new project is supported by a second grant (type A1 reinforcement).

Additional information

Project participants

Local women project leaders:

Teresa Peña, Elizabeth Fuentes, Ana Méndez, Rosa Lawrence, Maritza Contreras, María Salas, Ruth Godoy, Solange Villarroel, Ana Pinto, Elizabeth Valencia, Michelle Faulon, Marianela Soto, Eugenia Pinto, Iris Vargas, Margarita Carrasco.

Students:

I Stage Initial project idea. Subject Project Workshop II, year 2016: Student Iliam Delgado.

II Stage Preliminary architectural project: Iliam Delgado, Luciano Riquelme.

III Stage Construction development: Camila Soto, Constanza Jara, Diego Paredes, Constanza Sáez.

IV Stage Construction and Assembly: Valentina Ceballos, Carlos Morales, Ronald Baez, Darling Quitral, Benjamin Alvarado, Iliam Delgado, Adrian Erbo, David Godoy, Felipe Castillo.

Academics and professionals:

Neighborhoods Workshop Team: Claudio Araneda, Ignacio Bisbal (4th year); Roberto Burdiles, Nicolás Sáez (3rd year); Rodrigo Lagos, Luis Felipe Maureira (2nd year); Nelson Arias, Hernán Ascuí (1st year)

Team “Quiero mi Barrio Bellavista:”

Hilda Basoalto, Alfonso Galán, Alexi Valdebenito, Jorge Méndez.

Architecture firm República Portátil:

Luis Felipe Maureira, Andrés Moreno, Camilo Aravena, Marta Villaverde, Oscar Zambrano, Martin Mansilla

Local Government Laboratory UBB:

Carmen Burdiles (Executive Coordinator), Bárbara Ojeda (UBB Social Work Internship student)

Corporación Desarrollo Conciencia – Comisión Residuos Comité Comunal Ambiental de Tomé:

Valeria Roa, Felipe Roco